5 November 2024 – Happy Election Day

Book Research News

My last newsletter was in February – apologies for being quiet for so long. I’m moving forward with chapters for the book on China’s state security structure and activities, and will shortly submit a proposal to a publisher. The revised table of contents includes chapters on:

- Enemies Within (sound familiar?)

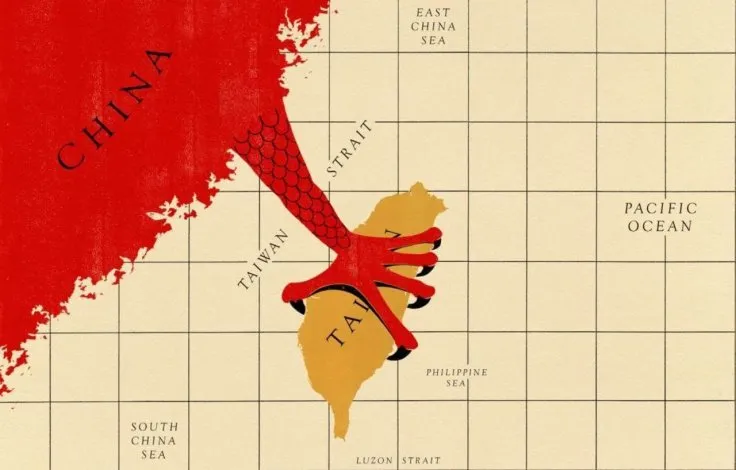

- Taiwan and the United States as main espionage targets

- The CCP’s use of Hong Kong and Macau

- Operations in Europe and Asia

- The Cyber Revolution

- Research Challenges

About Those Research Challenges

That last chapter is meant as a guide for graduate students, and ambitious undergrads, seeking dissertation and thesis topics in national security studies and Chinese politics or history. Many of the proposed subjects would require skill in reading Chinese, but not all. As I mentioned in the last newsletter, we need an institutional effort to advance focused studies of China’s public security and state security apparatus! That would encourage the next generation of scholars to continue open-source studies of this important topic.

By contrast, if inquiries stay within the classified world, then the public outside of China will remain forever mystified about this topic, and easily bamboozled with exaggerations and lies.

One of those research challenges is the life of Ji Chaoding (冀朝鼎): Ji is widely known as an important PRC economist who died a premature death in 1963, but before the 1949 victory, he spent two decades as a secret agent directly reporting to Zhou Enlai, first from the United States and Europe, and then from inside the Kuomintang government in China during World War Two. Ji may have played a part in recruiting Frank Coe, a U.S. Treasury Department employee, to work for the Soviets (Comrade Coe fled the U.S. for China in 1958 and lived the rest of his life there, translating Mao’s works into English. Another topic: why did Coe choose Beijing instead of Moscow?).

Ji Chaoding was the older brother of the more well-known Ji Chaozhu, one of the principal interpreters for Mao Zedong and Zhou Enlai. In his autobiography in English, Ji Chaozhu acknowledged his brother’s secret intelligence duties, which Chinese sources tend to gloss over. See Ji Chaozhu, The Man on Mao’s Right, easily found via online booksellers.

Meanwhile, here are a couple of items about how the Chinese tech scene and the business environment for foreign firms are rapidly changing – as CCP espionage has long been focused on clandestine technology acquisition, these are important sub-topics in CCP intelligence history.

Interested in China’s Drive for Technology Supremacy? Listen to Craig Allen on Chinese “Re-Innovation”

Craig is the President of the U.S.-China Business Council. He gave a talk (YouTube, here) at Stanford in May about the often misunderstood nature of China’s innovative technology culture. Craig listed elements of China’s “new productive forces” that “distinguish Shenzhen from Silicon Valley.” Among them:

- China’s acute labor shortage will only get worse, so the government is stimulating factory automation and efficiency in mature industries (important in China’s success in dominating the mature semiconductor market, vital to military production everywhere);

- the creation of new industries (e.g. semiconductors, robotics, lasers, all important dual-use technologies), in a manner not constrained by the market, at almost any cost in money and engineers;

- an overwhelming preference for self-reliance and import substitution, meaning that the role of foreign companies has become limited to investment that helps China “re-innovate” and create its own original technologies (see Tai Ming Cheung’s 2022 book Innovate to Dominate, for a full explanation about “re-innovation (再创新) and China’s drive for technology supremacy;

- a high level of government support for advanced technology;

- a lot more engineers are available to do it all, compared to the U.S.

Hard Business Lessons in China, with the Former CEO of Silicon Valley Bank

Ken Wilcox, the former CEO of Silicon Valley Bank, has penned a new book to be published next month. It’s available to pre-order, reasonably priced, and worth a look. The title is a good preview: The China Business Conundrum: Ensure That “Win-Win” Doesn’t Mean Western Companies Lose Twice. Ken gave a YouTube interview about his time at Silicon Valley bank here, and in print with The Wire China here.

Back to Spying: Excerpt, Talk on the Ministry of State Security

I gave a talk last month to the San Francisco Chapter of the Association of Former Intelligence Officers, with a slide show, about some of the basic things we in the unclassified world know about the MSS. Here is an excerpt, rewritten for the format of a newsletter. I invite your learned comments.

Chinese espionage organizations did significant work before the 1949 victory, playing an important role in the final years of the revolution,[1] including engineering a thorough infiltration of the Republic of China (ROC) establishment and planting a mole inside the US government—namely Larry Wu-tai Chin (金无怠). However, the early achievements of PRC intelligence organs in the 1950s and 60s were small in scope and number compared to those of the Soviets, the Americans, and other major powers.[2]

That situation has changed in the last two decades. Many of Beijing’s clandestine achievements are owed to their increasing use of cyber espionage beginning c. 2005, but their human intelligence (HUMINT) agent recruitment efforts seem also to have expanded both in volume and in international scope, as Beijing seeks to suppress dissident emigres, render criminals back to China, exert political influence abroad, and gather intelligence on a wider range of nations. Indeed, Xi Jinping’s more assertive foreign policy must be generating additional intelligence requirements. This is obvious, but we in the unclassified world who study these questions still know very little about the PRC intelligence cycle and the nature of tasking.

China’s IC (intelligence community) must fulfill requirements like those imposed on other major services, principally digging out secrets from foreign governments to inform Chinese Communist Party (CCP) decision-makers. However, China’s unique circumstances may influence intelligence tasking.

One of them is the legacy of the “century of humiliation” from the First Opium War through the 1949 communist victory. In part, that difficult time generated a need to catch up with foreign technological developments—by hook or by crook—creating a massive collection and reference system that involves not only the PRC IC but also wider parts of the Chinese techno-industrial complex, as described in the books by Hannas, Mulvenon, Puglisi, and Tatlow.[3]

Another is the insecurity in power of the CCP, not to mention their frail and fragile institutional ego. That and the longstanding tendency to perceive an endless selection of enemies within and abroad drives Beijing to spend enormous resources on goals unfamiliar to our concepts of national security. These include building a mass surveillance society at home, used to vehemently quash even the least significant opposition, and “the most sophisticated, global, and comprehensive campaign of transnational repression in the world” applied across at least 36 countries, according to Freedom House.[4]

Chen Wenqing (front, left), Politburo member and the CCP’s top intelligence official, at a Party School meeting in October. At the center is General Zhang Youjia, Politburo member and vice chair of the Central Military Commission. At right: General He Weidong, also a Politburo member and vice chair of the CMC.

As recently revealed by the large leak of documents from the hacking and intelligence contractor iS00N in Chengdu (see my previous newsletter from February 2024), expanded tasking to follow events abroad, particularly of Uyghurs and Tibetans, has been contracted out to businesses like iS00N in significant volume. A great series of articles can be found online at the website of the group Natto Thoughts, easy to find with a simple web search, and you can search my name and Jamestown China Brief, or my name and SpyTalk to read more about this.

As Minxin Pei (Poli Sci Department, Claremont-McKenna College) points out in his new book The Sentinel State, the highly sophisticated mass surveillance state in China today had favorable conditions for its establishment with the foundation laid down by the Leninist CCP under Mao, which for a decade looked to the Soviets for inspiration. Though there was a relative relaxation in the 1980s, the party renewed its attention to domestic security affairs after the 1989 Tiananmen Incident. And under Xi Jinping, technology has been applied as a force multiplier that has made “real-time surveillance—long an aspiration of the Chinese police—a reality.“[5]

As in Russia, the Leninist state made China an ultra-hard target for foreign espionage services. With the mounting paranoia about spying, China is becoming hazardous for NGOs, businesspeople, students, and hypothetically, even tourists, particularly if their home country and China suddenly face a bilateral confrontation. Taking hostages has long been a part of the CCP playbook, and under Xi Jinping and his policies, the risk of arbitrary detention has risen.[6]

As Nigel Inkster said in a recent episode of the British podcast Chinese Whispers, the MSS officer Xu Yanjun, who was nabbed in Belgium trying to steal American aerospace secrets, was “more Inspector Clouseau than James Bond.” Xu was lured to Belgium, where he initially hesitated to go, and fell into an FBI trap. Xu had his work mobile phone with him, handing the FBI all sorts of details about him, his employer—the Jiangsu State Security Department—and his mission to steal aerospace technology from General Electric and other companies.[7]

Xu Yanjun, left, and his accomplice Ji Chaoqun. The captions read: Xu Yanjun, Deputy Chief, 6th Bureau, Jiangsu State Security Department. Ji Chaoqun, a Beijing Aerospace and Aeronautical University graduate, obtained a Master’s in Electrical Engineering from the Illinois Institute of Technology.

The case of Xu and an agent in his network, Ji Chaoqun, revealed Xu’s use of commercial cover identities, his specific technology targets, and importantly, an ambitious task to recruit graduate students in the US who could go to work in American firms with the object of acquiring technologies of interest. These mistakes made by Xu were revealing, and one wonders if they will be repeated or rectified.

Professional espionage recruitment approaches on LinkedIn led to the case of Kevin Mallory, the former CIA officer and defense contractor who revealed defense secrets to China. Among the millions of unwanted “cold call” approaches, seen every week on that platform, almost all are plain old fraud attempts. But a small percentage are the real thing, a series that led to a public warning by the French government.

Analysts such as Nigel Inkster have long pointed out that most of the actual work done by the MSS is through their State Security Departments and Bureaus at the province and municipal and county levels, respectively—even the foreign intelligence work, as the Xu Yanjun case illustrates. In his 2016 book, Inkster listed the Shanghai SSB being focused on the United States, the Zhejiang SSD against Northern Europe, the Qingdao SSB against Japan and the Koreas, and so on.[8] But recent cases indicate that any neat turf divisions that once existed are being reviewed, possibly with assignments given to organizations that can simply do the mission as soon as possible. However, the iS00N case and others show that at least one Public Security Bureau tasked itself, or was tasked by Beijing, to keep tabs on its emigres abroad using a hacking contractor.[9]

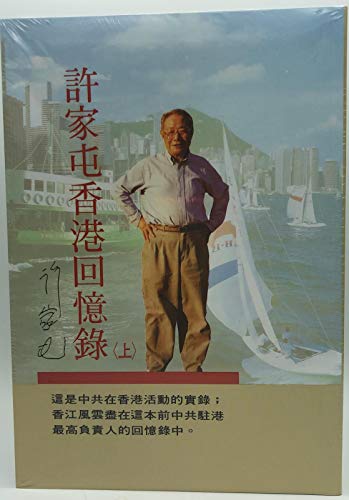

Finally, what can we make of all this? In the 1950s Zhou Enlai used secret annual conferences in Beijing to organize turf between the agencies to avoid duplication and conflict, an effort stymied by the Cultural Revolution. By the 1980s Hong Kong was a wild west of Chinese civilian and military intelligence organs, according to the memoir of Xu Jiatun – the head of Xinhua Hong Kong, and therefore the party’s senior cadre on the then British colony (he defected in 1990 and lived out his life in California).[10]

Xu Jiatun’s Memoir, Vol 2, published in Hong Kong but now only available secondhand.

It remains to be seen what Xi Jinping is trying to accomplish in the context of what appears to be a worldwide espionage and influence offensive. To make a long story short, other things that we might see as problems show little sign of changing. The uneven officer and agent training seen in the Xu Yanjun and Kevin Mallory cases may be representative of an astounding lack of care for officers and agents caught abroad (Xu, Chi Mak, Larry Wu-tai Chin, and many others).

One conclusion might be that top party officials may believe what they have now works for them, so why change it? Party propaganda about the revolution talks about their “nameless heroes of the hidden battlefront”[11] and Xi Jinping tells the youth of China that they ought to be more willing to “eat bitterness” and sacrifice for their country.[12] It may be that these elements will work together to prevent much change from what we see today, that is: escalating requirements, short-term albeit practical thinking, disregard for employees and recruited agents, and the lack of any hint of ethical conduct other than discouraging corruption—in a culture where corruption has so long been the norm.

—

Footnotes are further below.

Thanks for subscribing. See the bottom of this message if you wish to unsubscribe. You are welcome to pass this newsletter along to interested parties.

Non-resident Fellow, The Jamestown Foundation Contributing Writer, SpyTalk

California, US

Email: matthew.brazil@gmail.com Encrypted: matt.brazil@hushmail.com

https://www.mattbrazil.net/

https://www.usni.org/press/books/chinese-communist-espionage

[1]开诚, 李克农 中共隐蔽战线的卓越领导人 [Kai Cheng, Li Kenong, Outstanding Leader of the CCP’s Hidden Battlefront] (Beijing: Zhongguo Youyi Chubanshe, 2011) 266-267.

[2] Interview with Ambassador James R. Lilley at the American Enterprise Institute, Washington, DC, 2004.

[3] William C. Hannas, James Mulvenon, and Anna Puglisi, Chinese Industrial Espionage: Technology Acquisition and Military Modernization (Routledge, 2013). William C. Hannas and Didi Kirsten Tatlow, China’s Quest for Foreign Technology: Beyond Espionage (Routledge, 2020).

[4] Freedom House, “China” Transnational Repression Origin Country Case Study” https://freedomhouse.org/report/transnational-repression/china

[5] Minxin Pei, The Sentinel State: Surveillance and the Survival of Dictatorship in China (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2024) 19, 177.

[6] Christian Shepherd and Vic Chiang, “From Salesman to ‘spy’: An inside account of arbitrary arrests in China”. The Washington Post, 27 July 2023. https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/2023/07/27/china-taiwan-arbitrary-arrest-prison/. Matthew Brazil, “Thinking the Unthinkable: Are American Organizations in China Ready for a Serious Crisis?” Jamestown China Brief, Vol. 17, Issue 7, 11 May 2017. https://jamestown.org/program/thinking-unthinkable-american-organizations-china-ready-serious-crisis/

[7] Cindy Yu and Nigel Inkster, “What Chinese hackers want”, the Chinese Whispers podcast, 28 March 2024. https://www.spectator.co.uk/podcast/what-chinese-hackers-want/

[8] Nigel Inkster, China’s Cyber Power (Oxon: Routledge, 2016), 54-55.

[9] Matthew Brazil, “Foreign Intelligence Hackers and Their Place in the PRC Intelligence Community”, The Jamestown China Brief, 3 April 2024. https://jamestown.substack.com/p/foreign-intelligence-hackers-and

[10]许家屯 许家屯香港回忆录 [Memoirs of Hong Kong by Xu Jiatun] (Hong Kong: 聯經出版事業(股)公司,1999 ) 20, para. 6. https://www.google.com/books/edition/%E8%A8%B1%E5%AE%B6%E5%B1%AF%E9%A6%99%E6%B8%AF%E5%9B%9E%E6%86%B6%E9%8C%84/W_lrAAAAIAAJ?hl=en

[11] For example, Fujian Daily, “蔡威:隐蔽战线的“无名英雄” [Cai Wei: nameless hero of the hidden battlefront], 25 May 2016, dangshi.people.com.cn/n1/2016/0524/c85037-28375789.html

[12] Li Yuan, “China’s Young People Can’t Find Jobs. Xi Jinping Says to ‘Eat Bitterness’” New York Times, 30 May 2023. https://www.nytimes.com/2023/05/30/business/china-youth-unemployment.html