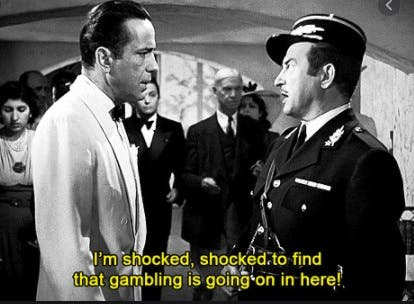

This year’s most popular poster at the MSS and the CCP Propaganda Department? Well, maybe only in the gift shop.

1. Sino Spies of the Baltic

Russian clandestine operations have long targeted the Baltic States and Scandinavia. But lately, the environment has become more crowded.

Interviews conducted in Europe since the last newsletter in July highlighted some interesting cases that will be detailed in the upcoming book. For example, in June 2023 Ms. Gerli Mutso was convicted of espionage on behalf of the PLA Joint Intelligence Bureau, the Chinese military’s human intelligence organization. She recruited an Estonian official with access to NATO classified information, traveling abroad several times for rendezvous to pass along data on “maritime” matters – probably related to the Arctic, where China seeks to build a presence.

That and other cases, some involving intimidating spying and influence operations in neighboring countries, are an indication of China’s proliferating worldwide espionage and influence activities.

An interesting wrinkle of the Mutso case: her handlers had her travel to China and Thailand to hand over the goods. They seem to have at least partly avoided potentially vulnerable electronic means of communication.

Thailand, incidentally, has been the scene of other CCP intelligence operations, which will be discussed in the upcoming book.

2. The comparative politics of spy trades

Interviews last year in Taiwan about CCP Intelligence operations revealed the same sort of agent-headquarters communication pattern. Chinese Communist operatives in Taiwan have long used couriers to communicate with handlers. Some other cases reflect this modus operandi. It seems to reflect a legacy of competence in clandestine communications going back to Chi Mak, Larry Chin (see below), and the Chinese Revolution itself. With the damage done to CCP Intelligence operations by the sloppy use of gadgets by at least one recruited agent and an MSS officer, courier-based communications may be making a comeback.

In various briefings over the past few years, I’ve included a list of similarities and differences between China’s premier civilian intelligence agency, the Ministry of State Security, and intelligence agencies in other countries.

The similarities include things like:

- collection against other countries’ state secrets in response to tasking by the national leadership;

- use by officers of both “legal” diplomatic cover and “illegal” non-official cover (NOC);

- false flag operations (pretending to work for a relatively palatable third country’s intelligence service);

- use of blackmail and monetary payments to facilitate agent recruitment.

But China’s services also stand apart from most other major powers. They:

- avoid acknowledging their foreign intelligence activity, almost always pretending that China is above it all. As Michael Schoenhals has pointed out, the UK also used to deny everything, albeit over a generation ago;

- pretend that China’s agencies eschew the “honey trap,” i.e. setups to enable sexual blackmail of a potential agent;

- reject spy trades to rescue their officers and assets caught abroad;

- prioritize state-led technology acquisition for military use and the commercial gain of PRC firms;

- enable public and private institutions and individuals to engage in industrial espionage and related activities.

One aspect that captures the imagination is Beijing’s continuing reluctance to admit that they engage in any foreign intelligence operations, and accompanying that stance, a reluctance to conduct spy trades when one of their own is caught abroad.

Yes, they traded Canada’s “Two Michaels” for the photogenic Huawei CFO, Ms. Meng Wanzhou (孟晚舟), but it appears that no one in this unfortunate trio was likely engaged in intelligence duties. Moreover, the end game (the Michaels being released as soon as Meng was allowed to return to China after admitting to financial fraud) strongly suggested that Beijing was baldly taking hostages and releasing them for the ransom of allowing a confessed criminal to go free.

That’s typical because the Chinese side is long notorious for arbitrary acts of nastiness against foreigners at home and abroad, including hostage-taking and random accusations of spying.

Meanwhile, there arises an accusation that one of the Michaels (Spavor), who is a Canadian former diplomat, reported his conversations with Michael Kovrig about the latter’s travels in North Korea, including a conversation over drinks with Kim Jong-un.

Just my opinion, but – why wouldn’t he? Unfortunately, it is no surprise that the Chinese side turned typical diplomatic reporting into a spying allegation.

Will Beijing let Xu Yanjun die in prison as they did Larry Chin and Chi Mak?

Getting back to spy trades: if we examine only the U.S.-China bilateral, China has let a number of their people rot or die in custody, notably Larry Wu-tai Chin (金无怠), Bernard Boursicot, Chi Mak (麦大志) and most recently Xu Yanjun (徐延军). Beyond them, the list is long.

Mr. Xu, or at least his spouse and child, undoubtedly hope for a trade between Washington and Beijing involving Xu and an accused spy for America, John Leung, (梁成运) now held behind bars in China. But by making such a trade would Beijing be tacitly admitting to spying? And would Beijing then start grabbing hostages to trade for their imprisoned, recruited agents?

3. Pathbreaking Research from Australia

The case for an open-source intelligence agency, or at least something much larger than exists today, continues to be made in this understudied field by scholars such as Nick Eftimiades and Peter Mattis. Some excellent research has emerged in the last 18 months from Alex Joske, the young Australian scholar of modern-day Chinese Communist espionage and influence operations who relies primarily on carefully selected Chinese language open-source info. In Spies and Lies, reviewed here and elsewhere, Alex made a major contribution by showing how the Ministry of State Security (MSS) has, for decades, engaged in influence work abroad.[1]

A few months ago, he published another work about the formation of State Security departments at the provincial and municipal level in China: “State security departments: the birth of China’s nationwide state security system” (Deserepi 0, 2023). His paper has new information on the predecessor of the Ministry of State Security, the Central Investigation Department (1955-1983), the work it did inside China, and how Investigation Departments at the local level were an important foundation of MSS from the beginning in 1983-84.

Another of many findings: Contrary to conventional wisdom, Public Security organs “contributed expertise in foreign intelligence operations, surveillance, and technological research—not just counterintelligence and security work—to the state security system.”

And finally

The book is coming along but remains a work in progress. I’ve been doing some restructuring to make it more readable but it is still intended to start as a brief narrative history of CCP Intelligence with a more lengthy analysis of Beijing’s present-day intelligence community.

More later.

Thanks for reading. If you wish to subscribe to the newsletter with this content, leave me a message on the contact page of this website or write to matthew.brazil@gmail.co